This information can also be viewed as a PDF by clicking here.

This factsheet is intended to provide access to relevant evidence-based information. The national guidelines, research, data, pharmacokinetic properties and links shared are taken from various reference sources, they were checked at the time of publication for appropriateness and were in date. These are provided where we believe the information may be useful but we do not take any responsibility for their content. This factsheet is provided to empower users to make an informed decision about their treatment; but it does not constitute medical advice and cannot replace medical assessment, diagnosis, treatment or follow up from appropriately trained healthcare professionals with relevant competence.

The Breastfeeding Network factsheets will be reviewed on an ongoing basis, usually within three years or sooner where major clinical updates or evidence are published. No responsibility can be taken by the Breastfeeding Network or contributing authors for the way in which the information is used.

If you have any questions about this information, you can contact the Drugs in Breastmilk team through their Facebook page or on druginformation@breastfeedingnetwork.org.uk.

The prescription of domperidone should be avoided in the following situations (1-3); Before prescribing domperidone other measures to increase milk supply should be in place. These include an assessment by someone skilled in breastfeeding support alongside expressing both breasts, at least 8 times in 24 hours including overnight. The maximum dose as a galactagogue should be 10mg three times a day. This prescription should be reviewed at 7 days and further prescriptions should be considered at a reducing dose. Mothers should be counselled as to the adverse effects of domperidone (abdominal cramping, dry mouth, depressed mood and headache) and advised to report any changes in their baby’s behaviour immediately |

Domperidone is a drug prescribed for nausea and vomiting. It also speeds emptying of the gut (prokinetic). Until September 2014 it was sold over the counter in the UK. It is not licensed for any indication in the USA because of concerns about arrhythmia. Domperidone has been prescribed off label for babies with reflux.

Following a European Review by PRAC (1) the MHRA updated their advice on the prescription of domperidone in May 2014 (5). They advise that domperidone is associated with a small increased risk of serious cardiac side effects. These have been reported predominantly in over 60s who had cardiac problems, were taking other drugs which also cause arrhythmia or were taking a dose of domperidone greater than 10mg three times a day (6, 7).

However: So individual prescribing decisions should be made bearing in mind the recommendations of MHRA and the risk to mother and baby of not establishing full lactation |

Side effects

Other than those identified by MHRA, side effects are rare – they include stomach cramps, dry mouth, headache and occasionally domperidone is associated with depressed mood (although less than metoclopramide).

Evidence of effectiveness

Domperidone has been used as a galactagogue (to increase milk supply), use for which is off-label, utilising its effect of increasing prolactin. You can read information on using domperidone to treat low milk supply from the NHS specialist Pharmacy Service (SPS) here.

Studies have predominantly been around use in mothers of preterm infants who are struggling to establish lactation 2 to 4 weeks after delivery. The studies have shown that domperidone is effective in increasing breastmilk production. Very small amounts of domperidone pass into breastmilk. The amount depending on the dose that the mother takes. Decision to prescribe for domperidone is the responsibility of the person signing the prescription. This document aims to provide sufficient information for individual decision making bearing in mind the risk to the mother and baby of not breastfeeding compared to the possible risk of the drug. There is no evidence of increased risk to health young women who do not fall into any of the at risk categories (8)

“Of the thousands of mothers the authors of this statement have collectively treated with domperidone for the purposes of breastfeeding support, no one is aware of a single case of maternal death from ventricular arrhythmia. In fact, Health Canada’s Canada Vigilance Program has confirmed that between 1965 and 2011, there were no cardiac-related deaths reported among women taking Domperidone”

Osadchy (9) reviewed 3 randomised controlled trials (DaSilva (10), Campbell-Yeo (11) and Petrolagia(12)) involving a total of 78 participants. The results showed a relative increase in breastmilk production of 74.72% over placebo. The study periods varied between 7 and 14 days. Only one study (Petrolagia(12)) referred to lactation counselling prior to prescription of medication or placebo. No follow up data on outcomes after the study period are available.

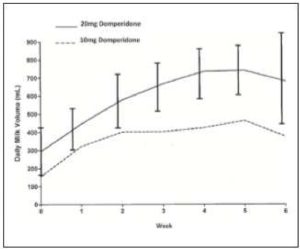

Fig. 1 Milk volume as a function of dose

(Reproduced from Knoppert (13)

Knoppert(13) studied pre-terms to determine the optimal dosage of domperidone as a galactagogue randomising women to a regime of 10 or 20mg three times a day for 4 weeks. Following the study period the dose was tapered to a twice daily then daily regime before stopping. At the end of 4 weeks there was no statistically significant difference in the increased milk volumes between the 2 groups but the study was not powered to demonstrate this because of the number of women involved.

There was a statistical difference in prolactin levels in both cohorts between baseline and day 10. Mothers excluded from the study were those taking anti arrhythmia drugs, who had a family history of arrhythmia, were taking quinolone antibiotics, or drugs metabolised by CYP 3A4 e.g. ketoconazole, macrolide antibiotics. They were required to be pumping a minimum of 8 times in 24 hours. Following the cessation of the drug 4 mothers continued to measure milk volume – 3 maintained their supply one dropped from 750ml per day to 500ml per day. Only one mother exhibited a side effect of nausea which resolved when she took the medication with food.

Campbell-Yeo (11) studied the composition of breastmilk following maternal use of domperidone. She analysed the macronutrient content with respect to protein, fat, carbohydrate and energy and macro mineral content of sodium, phosphorous and calcium of 44 women taking either 10mg three times a day of domperidone or placebo. Domperidone increased the volume of breast milk without substantially altering the nutrient composition.

In the DaSilva study (10) 20 women in a double-blind, placebo-controlled protocol. Those prescribed domperidone 10mg three times a day showed a steady increase in milk production over placebo. Mothers received counselling support and were double pumping. The increase in production achieved fell once the drug was stopped after seven days. The babies in the study were all in neonatal intensive care and the mothers were only expressing for feeds to be given via naso-gastric tube. The increase in milk volume began 48 hours after the drug was initiated and continued to the end of the trial. The study was stopped after seven days when most mothers began some level of direct breastfeeding, at which point it became impractical to measure breastmilk volume.

Only one study looked at mothers who had not delivered prematurely (12). One month after the study began all treated women had adequate milk production, but none of those who had not been treated with domperidone had achieved an increase in milk supply above that at the beginning of the trial.

Wan et al (14) studied seven mothers who had delivered pre-term in a double-blind, randomised cross-over study. They used two dose regimes – 10mg or 20mg three times a day. One mother taking the 20mg dose withdrew early because of severe abdominal cramps. Two others failed to respond to either dose. In four mothers, there was a significant increase in prolactin level and milk volume, with a greater response at the higher dose in three of these women. Side effects noted included abdominal cramping, constipation, dry mouth, depressed mood and headache, which were more apparent with the higher dose. Wan et al (2008) concluded that if there is no response at a 10mg dose, there is no point in further increasing the dose. This is at variance to the information in the consensus statement (8).

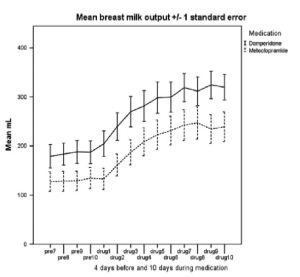

Fig. 2 Average milk output (ml per 24 h) over the medication phase of the study for mothers taking domperidone or metoclopramide (drug days 1–10) and for 4 days before (pre-7 to pre-10).

(Reproduced from Ingram (15))

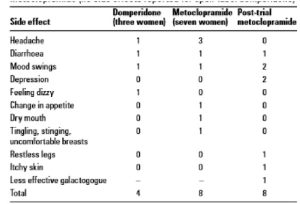

Ingram (15) studied eighty mothers expressing breast milk for their infants (mean gestational age 28 weeks) based in NICU and the amounts expressed fell short of the infant’s needs. Mothers produced more milk in the domperidone group and achieved a mean of 96.3% increase in milk volume compared with a 93.7% increase for metoclopramide. This difference was not statistically significant. Ten women (15.4%) reported 12 side effects when taking the medication. Headache by 1 on domperidone 3 on metoclopramide, 1 on each medication reported diarrhoea, one on each mood swings, one mother on domperidone reported dizziness. Other effects reported by the metoclopramide cohort were change in appetite, dry mouth, and tingling, stinging, uncomfortable breasts. Only one woman stopped taking the trial medication (metoclopramide) after 5 days due to bad headaches and dry mouth; all the others tolerated any side effects as they were keen to keep their increased milk production going.

Amount of domperidone in breastmilk

Very small amounts of domperidone pass into breastmilk. DaSilva (16) reported average milk concentrations ranged from 1.2 micrograms/L (1) to 2.6 micrograms/L. in babies whose mothers had taken domperidone 10mg three times a day for 5 days. No adverse events were noted in mothers or children. Domperidone is subject to extensive first pass metabolism which accounts for the low transfer into breastmilk. The mean relative infant dose was 0.01% after a 30 mg daily dose and 0.009% at 60 mg (14). Hale (17) quotes a relative infant dose range of 0.01% – 0.04%, well below the 10% regarded as significant.

Weaning from domperidone

There are no studies that provide an evidence base on how long to continue domperidone in the case of inadequate lactation (18). Anecdotally, some women feel that their supply cannot be maintained without the drug, while some can reduce the dose but not stop altogether. It is possible that domperidone is acting as a placebo to boost their confidence – we do not know and should admit the limitations of the research.

After a slow withdrawal from domperidone, one study found no significant increase in formula supplementation suggesting that once sufficient milk production is established, it is maintained even without the use of domperidone (19).

Knoppert (10) showed that in 3 out of 4 women who had taken domperidone for 4 weeks at full dose, 2 weeks at reducing dose, milk supply was maintained. Although gradual weaning from the drug has become standard, there is little evidence apart from the reports and experience of breastfeeding specialists.

Table 3 reported side effects from trial drugs (reproduced from Ingram)

Other drugs to increase milk supply

Domperidone is preferred to metoclopramide because it poorly penetrates the blood-brain barrier and does not produce parkinsonian-like adverse effects or increase the risk of depression (17). The amount passing through breastmilk is significantly less than the dose prescribed directly to babies to control symptoms of reflux.

Domperidone is preferred to metoclopramide because it poorly penetrates the blood-brain barrier and does not produce parkinsonian-like adverse effects or increase the risk of depression (17). The amount passing through breastmilk is significantly less than the dose prescribed directly to babies to control symptoms of reflux.

Review of recommendation on safety of domperidone 2011 in the consensus statement by breastfeeding experts

“The recommendation 2011 (20) is based on data derived from two public health databases: one in the Netherlands (6) and one in Saskatchewan (7). The warning was based on information gathered from an entirely different population than those who would be taking domperidone for breastfeeding purposes and is thus not generalizable to the lactating population.

The average age of the patients in the studies was 72.5 years in one and 79.4 years in the other. Many of the patients in the studies had pre-existing health problems such as high blood pressure, coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure. There were, however, some notable trends that, when extrapolated to the breastfeeding population largely comprised of younger healthier women, are quite reassuring. In one study, the authors concluded that the risk of a cardiac problem related to taking domperidone in younger patients was much lower than in older patients. In fact, the risk quoted in younger patients was almost the same as that outcome occurring by chance alone (OR of 1.1 in those younger than age 60 compared with an OR of 1.64 in those older than age 60). That study also specifies that the risk in females was significantly lower than in males (OR of 1.25 in females compared with an OR of 2.23 in males.

The warning regarding the use of domperidone in higher doses (>30mg per day) was based on only one of the two studies; the other study did not include any information about dosing. In the one study where dosing information was included, out of the 1304 deaths that were studied, only 10 patients were taking domperidone at the time of death. Of those 10 taking domperidone, only 4 patients were documented to be taking higher doses of domperidone (>30mg per day). Thus, this Health Canada-endorsed doserelated warning comes from dosing data compiled from a total of four patients. In fact, the authors were not specifically cautioning physicians not to prescribe higher doses, but rather were suggesting that “it is important to avoid prescribing domperidone to patients with a high risk of sudden cardiac death”. It is very hard to make a case for a drastic reduction in domperidone dosing in lactating women (wherein a dose of <30mg may not be sufficient to support lactation in a significant number of cases) when the data relied upon to generate the dosing warning was based on such a small number of cases that do not demographically resemble the population in which it is being prescribed. “

Conclusion

Domperidone is not a ‘magic wand’ to increase the milk supply of a mother struggling to breastfeed, and it should not be used unless accompanied by regular and effective drainage of milk from the breast. It may be a valuable tool to support mothers who have delivered pre-term and who maintain their lactation over a prolonged period by expression, or mothers who have had a poor start to breastfeeding who need to relactate to some extent. It is also useful for women with identified hormonal difficulties that could affect milk supply, e.g. hypothyroid and polycystic ovaries.

Domperidone is a relatively safe drug, but it would be unethical and unprofessional to expose a mother and baby to a drug they do not need, and all measures to improve breastfeeding management should be made and documented prior to a decision to advocate its use.

References

- European Medicines Committee. March 2014 https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/prac-recommends-restricting-use-domperidone

- Website flash and short UKDILAS statement downloaded June 2014 from http://www.ukmi.nhs.uk/activities/specialistServices/default.asp?pageRef=2

- Evidence Summary Domperidone downloaded June 2014 from www.ukmi.nhs.uk/activities/specialistServices/default.asp?pageRef=2

- Drug Induced QT interval www.ggcprescribing.org.uk/media/uploads/ps_extra/pse_21.pdf

- MHRA information for patients www.mhra.gov.uk/home/groups/dsu/documents/publication/con418525.pdf

- van Noord C et al. Domperidone and ventricular arrhythmia or sudden cardiac death: a population-based case-control study in the Netherlands. Drug Saf. 2010 Nov 1; 33(11): 1003-1014.

- Johannes CB et al. Risk of serious ventricular arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death in a cohort of users of domperidone: a nested case-control study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010 Sep; 19(9): 881-888

- Consensus statement by breastfeeding experts on Health Canada advice. May 2012. https://kindercare.ca/wp-content/uploads/Domperidone-Consensus-Statement-Final-May-11-2012.pdf

- Osadchy A, Moretti ME, and Koren G Effect of Domperidone on Insufficient Lactation in Puerperal Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Obstetrics and Gynecology International Volume 2012

- da Silva OP, Knoppert DC, Angelini MM et al. (2001) Effect of domperidone on milk produc- tion in mothers of premature newborns: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. CMAJ 164(1): 17-21

- Campbell-Yeo ML, Allen AC, Joseph KS et al. (2010) Effect of domperidone on the composition of preterm human breast milk. Pediatrics 125(1): e107-114.

- Petraglia F, De Leo V, Sardelli S et al. (1985) Domperidone in defective and insufficient lactation. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 19(5): 281-7.

- Knoppert DC, Page A, Warren J, Carr M, Angelini M, Killick D, DaSilva OP, The Effect of Two Different Domperidone Doses on Maternal Milk Production published online 3 May 2012J Hum Lact http://jhl.sagepub.com/content/29/1/38.full.pdf+html

- Wan EW, Davey K, Page-Sharp M et al. (2008) Dose-effect study of domperidone as a galactagogue in preterm mothers with insufficient milk supply, and its transfer into milk. Br J Clin Pharmacol 66(2): 283-9.

- Ingram J, Taylor H, Churchill C, Pike A, Greenwood R, Metoclopramide or domperidone for increasing maternal breast milk output: a randomised controlled trial Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed F2 of 5(2011). doi:10.1136/archdischild-2011-300601

- da Silva OP, Knoppert DC. (2004) Domperidone for lactating women. CMAJ 171(7): 725

- Hale T. Medications and mothers’ milk

- Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine (ABM) Protocol Committee. (2011) Use of galacto- gogues in initiating or augmenting the rate of maternal milk secretion (First Revision January 2011). Breastfeed Med 6(1): 41-9

- Livingston V, Blaga Stancheva L, Stringer J. The effect of withdrawing domperidone on formula supplementation. Breastfeeding Med. 2007; 2:278, Abstract 3.

- Mathivanan M. Health Canada Endorsed Important Safety Information on Domperidone Maleate. 2012 Mar 2 < https://recalls-rappels.canada.ca/en/alert-recall/domperidone-maleate-association-serious-abnormal-heart-rhythms-and-sudden-death>

Other references consulted

- Akre J. (1989) Infant feeding. The physiological basis. Bull World Health Organ 67 Suppl: 1-108.

- Amir LH. (2006) Breastfeeding – managing ‘supply’ difficulties.

- Aust Fam Physician 35(9): 686-9. Anderson PO, Valdes V. (2007) A critical review of pharmaceutical galactogogues. Breastfeed Med 2(4): 229-42.

- Cox DB, Owens RA, Hartmann PE. (1996) Blood and milk prolactin and the rate of milk synthesis in women. Exp Physiol 81(6): 1007-20.

- Gabay MP. (2002) Galactogogues: medications that induce lactation. J Hum Lact 18(3): 274-9.

- Hoddinott P, Tappin D, Wright C. (2008) Breast feeding. BMJ 336(7649): 881.

- Kramer MS, Kakuma R. (2002) Optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD003517.

- NHS Specialist Pharmacy Service: Using domperidone for low milk supply. https://www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/using-domperidone-for-low-milk-supply/

Ways to increase breastmilk supply without drugsEnsure the baby is well attached to the breast and is feeding effectively and frequently If the mother smokes encourage her to stop, since nicotine reduces milk supply. |

©The Breastfeeding Network. Last full review Sept 2019. Last updated July 2024.